The story of creation presents the basic principles of human life and behavior. It is the main reference for the Christian understanding of humankind’s existential questions. In the book of Genesis, the unique relationship between humans and their Creator unfolds. Inside it, the mystery of the purpose of this world is hidden, as is the destiny of our existence.

According to Genesis, God created everything in this world to be in the service of His beloved creature, the human person. Humans are the purpose of the whole of creation. God created the perfect environment for His most precious creature and wanted to share with it His Divine life. Creation of humanity is a special creative act of God that was made in steps[1] in contrast to the creation of all other things, which was performed immediately, with just one word. The importance of man’s creation is indicated by the fact that this act is preceded by a divine thought according to which man is created after God’s image[2]. Nothing else in the story of creation is comparable with the special care that the Creator took for His beloved creature.

The account of Genesis, which is the primitive history of human destiny in all ages, has been interpreted in so many different ways, with strengths and weaknesses in each point of view. Despite the method of examining the text – linguistic, historic, theological, sociological etc. – and trying to be fair to the text, when the author refers to the principles of human life or human characteristics in general, he uses the word ἂνθρωπος (human) without gender distinction. Thus, we learn that humanity (ἂνθρωπος) was created in the image and likeness of God, and was created with gender bipolarity[3]. He[4] was made out of dust, and received God’s breath into his nostrils[5]. God put His creature into Paradise and asked that he protect and cultivate it[6]. God then commanded Adam that they[7] not eat from the tree of “knowing good and evil” because doing so will cause death[8].

In a second account of creation, a detailed description of the creation of woman from the side of Adam[9] is provided. The creation of woman was also preceded by a divine thought: Adam should not be alone; God will give him a helper[10]. This helper, according to some interpreters, reflects God’s will to assist His creature and must be seen as divine providence and care for His creation[11]. Nevertheless, for others, the word “helper”, together with the expression “according to him” (κατ᾿ αὐτόν), is interpreted as a means of supporting the opinion that woman was created to meet man’s needs. This suggestion is not faithful to the text because in the Scripture the word “helper” can be used to refer to someone superior (God, angels), inferior (animals), or equal (another human being) to the human person in need of help[12]. Accordingly, now woman must be seen as a helper to man of the same rank[13] and both share the responsibility to work together. This view is supported by the text itself, since Adam was looking for a helper who would be the “same” as him (ὃμοιοs)[14]among the living creatures that God brought before him. The same interpretation is given by St. John Chrysostom[15] who wrote extensive commentaries on Genesis as well as on marriage.

[1] See more in E. Pentiuc, Jesus the Messiah in the Hebrew Bible, (Mahwah, 2006), 5.

[2] «καί εἶπεν ὁ Θεός΄ποιήσωμεν ἂνθρωπον κατ΄ εἰκόνα ἡμετέραν καί καθ’ ὁμοίωσιν» Gen 1:26.

[3]«..καί ἐποίησεν ὁ Θεός τόν ἂνθρωπον, κατ’ εἰκόνα Θεοῦ ἐποίησεν αὐτόν, ἂρσεν καί θῆλυ ἐποίησεν αὐτούς» Gen 1: 27.

[4] “He” does not refer to the male gender, but expresses the masculine word “ἂνθρωπος”, which refers to all humans.

[5] «καί ἒπλασεν ὁ Θεός τόν ἂνθρωπον, χοῦν ἀπό τῆς γῆς, καί ἐνεφύσησεν εἰς τό πρόσωπον αὐτοῦ πνοήν ζωῆς, καί ἐγένετο ὁ ἂνθρωπος εἰς ψυχήν ζῶσαν» Gen 2:7.

[6] «Καί ἒλαβε Κύριος ὁ Θεός τόν ἂνθρωπον, ὃν ἒπλασε, καί ἒθετο αὐτόν ἐν τῷ παραδείσω τῆς τρυφῆς, ἐργάζεσθαι αὐτόν καί φυλάσσειν» Gen 2:15.

[7] Changed to plural because the reference is both to man and woman.

[8] «καί ἐνετείλατο Κύριος ὁ Θεός τῷ Ἀδάμ λέγων’ ἀπό παντός ξύλου τοῦ ἐν τῷ παραδείσω βρώσει φαγῇ, ἀπό δέ τοῦ ξύλου τοῦ γινώσκειν καλόν καί πονηρόν, οὐ φάγεσθε ἀπ’ αὐτοῦ’ ᾓ δ᾿ ἂν ἡμέρα φάγητε ἀπ᾿ αὐτοῦ, θανάτω ἀποθανεῖσθε» Gen 2:16-17.

[9] «καί ἒλαβε μίαν τῶν πλευρῶν αὐτοῦ καί άνεπλήρωσε σάρκα ἀντ᾿ αὐτῆς. Καί ᾠκοδόμησεν ὁ Θεός τήν πλευράν, ἣν ἒλαβεν ἀπό τοῦ Ἀδάμ, εἰς γυναῖκα καί ἢγαγεν αὐτήν πρός τόν Ἀδάμ» Gen 2:21,22.

[10] «Καί εἶπε Κύριος ὁ Θεός΄οὐ καλόν εἶναι τόν ἂνθρωπον μόνον΄ποιήσωμεν αὐτῷ βοηθόν κατ᾿ αὐτόν» Gen 2:18.

[11] Pentiuc, Jesus the Messiah, 15.

[12] Theodosios Haralampopoulos, Περί της Θέσεως της Γυναικός Έναντι του Ανδρός κατά τηνΟρθόδοξον Χριστιανικήν Εκκλησίαν καί περί Φόβου Θεού (Αθήνα: 2004), 7-9.

[13] This is what is meant by the expression “κατ᾿ αὐτόν”.

[14] «τῷ δέ Ἀδάμ οὐχ εὑρέθη βοηθός ὃμοιος αὐτῷ» Gen 2:20.

[15] «…Τό μέλλον δημιουργεῖσθαι ζῶον τοῦτό ἐστι περί οὗ ἒλεγε΄ “ποιήσωμεν αὐτῷ βοηθόν κατ᾿ αὐτόν”, ὃμοιον αὐτῷ φησι, τῆς αὐτῆς αὐτῷ οὐσίας, ἂξιον αὐτοῦ, μηδέν αὐτοῦ λειπόμενον…Οὐκέτι γάρ εἶπε “ἒπλασεν” ἀλλ᾿ “ᾠκοδόμησεν” ΄ἐπειδή ἐκ τοῦ ἢδη πλασθέντος τό μέρος ἒλαβε ΄καί, ὡς ἂν εἲποι τις, τό λεῖπον ἐχαρίσατο…καί τέλειον καί ὁλόκληρον καί ἀπηρτισμένον κατασκευάσαι, τό δυνάμενον καί προσδιαλέγεσθαι καί τῇ τῆς οὐσίας κοινωνία πολλήν αὐτῷ τήν παραμυθίαν εἰσφέρειν» “Εἰς Γέν., Ὁμιλία ΙΕ” PG 53, 120-122.

2. Eve The Helper

The word “helper” itself presupposes an action for which Adam needs help. The only work that the text refers to is to protect and cultivate Paradise. The first interpreters of the sacred text understood that labor in Paradise was not handy work, but spiritual effort, meaning a labor toward perfection. According to several Christian writers, the human person was created physically perfect, but spiritually imperfect. St. Irenaeus of Lyons believed that the first man and woman were not made morally perfect from the beginning because in that case all their actions would have no moral significance[1]. “Though they were made having the image and likeness as their potentiality, they were required to become the image and likeness through spiritual labor and their free choice”[2]. “And the order to ‘till (work) it’ refers to no other labor than the keeping of God’s commandment”[3]. Woman therefore was created to work together with Adam toward their spiritual growth. This is, according to the Fathers, why Eve was punished to be ruled by man in Gen. 3:16[4]. That is to say, instead of being an assistant to Adam’s spiritual development, she became a temptress and caused his fall.

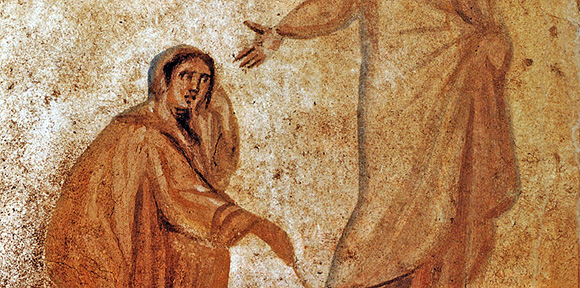

Wenceslas Hollar – Creation of man and beast (unknown date, author lived 1607-1677)

After woman’s creation, Adam rejoiced that he finally (νῦν) found the help that God had promised him. He then proclaimed and prophesied the destiny of this unity of the two[5]. Man and woman are meant to be one flesh, reshaping the face of humanity as God had originally intended — one human nature. We have here the institution of marriage with some innovative sociological insights. In the ancient Near East, a woman was to leave her family and join her husband’s. Contrary to this custom, Adam commands men to leave everything and follow their wives. Nevertheless, this unity in one “flesh” contains the element of transience because “flesh” is temporary and mortal. Therefore, marriage is an institution for this present world and does not extend to the next life. For Saint John Chrysostom, man and woman are parts of the whole of humanity; both are incomplete in different ways from each other. They need the other part in order to be complete and their perfection depends on the unity of the two[6]. In Biblical typology, God is the νυμφαγωγός[7] of the first couple and of all couples in all ages.

The Septuagint remained faithful to the original Hebrew text and translated the word adam (fromadama, which means ground) with the word ἂνθρωπος (human person). The authors change to the proper name Ἀδάμ (Adam) only in chapter 2:16 because from there the story of woman’s creation is introduced beginning with God’s plan that man should not be alone. Nevertheless, according to some interpreters, in the Hebrew text the word adam is not used as a proper name but with its literal meaning “humanity” or “people”[8]. Accordingly, woman was not created from the side of man (Adam) but from the side of the first human person. Thus, the proclamation of Adam that woman (issa) was created from man (is) makes it appear that this is a sociological influence inserted into the text[9]. This obstacle for the interpreters of the Hebrew text gave rise to the idea that the first human person was created as an androgynous being. However, this idea was never adopted by Christian theology.

The unique creation of the human person in the image and likeness of God is a great honor bestowed by God to humanity, but a difficult issue for the interpreters of the text. Although the double expression: besalmenu kidemutenu in Gen. 1:26 connects the descriptive saelaem (plastic picture, image) with the abstract demut (similarity, likeness)[10] as they have two different meanings, the translation of the Septuagint indicates the use of the terms “image” and “likeness” as interchangeable[11]. Nevertheless, the patristic interpretation understands “image” as given in the act of creation, while “likeness” has to be accomplished by the will of the human person working with God. Use of the descriptive word saelaem (plastic picture, image) in the text should not lead us to say that it is an attempt to present an anthropomorphism of God. On the contrary, it is a theomorphism of the human person[12]. The main point in the narrative is that the human person is not self-sustaining but comes from God and lives a transparent life in His presence. Humanity came into existence from the beginning, sharing something with its Creator (His breath[13]) and representing God in this world according to the original meaning of the word saelaem[14].

After the Bible, Tatian was the first of the Christian writers to use the terms “image and likeness,” and understood them as referring to the Holy Spirit which made man to share in God’s immortality. After the fall, humans were separated from God’s Spirit and became mortal[15]. “For man had been made a middle nature, neither wholly mortal nor altogether immortal but capable of either”[16]. According to Professor John Romanides: “Moral perfection and immortality […] constitute the whole basis of understanding the image and likeness of God and the early Christian doctrine of the fall and salvation”[17]. In spite of various interpretation of the image and likeness of God, we can see this as a cross with the horizontal dimension referring to the unity of human nature[18] and the vertical dimension referring to our relationship with God[19].

The beloved creatures were put into Paradise to enjoy happiness with only one restriction. There was a fruit that was forbidden to them. The tree of “knowing good and evil” is only mentioned in Genesis and nowhere else in Scripture. Saint Theophilus of Antioch says: “… the tree of knowledge itself was good, and its fruit was good. For it was not the tree, as some think, but the disobedience which had death in it. For there was nothing else in the fruit but knowledge; knowledge, however, is good when one uses it discreetly”[20]. In the Old Testament, knowledge is not theoretical and objectively far from the subject, but includes the subject [21] some times in a very materialistic way such as the knowing of Eve by Adam “now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain”[22]. Accordingly, in the Old Testament, knowing God is to be known by God and presupposes a mutual relationship. Thus, the knowing of God comprises a personal characteristic of mutual recognition. The same must apply in the case of the knowing of good and evil. This is how sin and evil entered human life.

[1] J. Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, (Ridgewood, 2002), 126.

[2] Irenaeus, Refutation quoted in Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, 158.

[3] St. Theophilus of Antioch, To Autolycus, in Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, 125.

[4] «πρός τόν ἂνδρα σου ἡ ἀποστροφή σου, καί αὐτός σου κυριεύσει» Gen 3:16.

[5] «τοῦτο νῦν ὀστοῦν ἐκ τῶν ὀστέων μου καί σάρξ ἐκ τῆς σαρκός μου ‘ αὓτη κληθήσετε γυνή, ὃτι ἐκ τοῦ ἀνδρός αὐτῆς ἐλήφθη αὓτη’ ἓνεκεν τούτου καταλείψει ἂνθρωπος τόν πατέρα αὐτοῦ καί τήν μητέρα καί προσκολληθήσεται πρός τήν γυναῖκα αὐτοῦ, καί ἒσονται οἱ δύο είς σάρκα μίαν» Gen 2:23,24.

[6] More about Chrysostom’s interpretation on marriage in S. Papadopoulos, “Ὁ Γάμος: Μυστήριο Ἀγάπης καί Μυστήριο «εἰς Χριστόν» (Θεολογική προσέγγιση τοῦ μυστηριακοῦ χαρακτήρα τοῦ Γάμου)” in the book Ιερά Σύνοδος της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος, Ὁ Γάμος στήν Ὀρθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία,(Αθήνα, 2004).

[7]The one who brings the bride to the groom.

[8] Pentiuc, Jesus the Messiah, 8.

[9] Ibid., 21.

[10] W. Zimmerli, Ἐπίτομη Θεολογία τῆς Παλαιᾶς Διαθήκης, Μετάφραση Π. Στογιάννος, Β΄ Έκδοση, (Αθήνα, 2001), 42.

[11] Pentiuc, Jesus the Messiah, 9.

[12] Zimmerli, Ἐπίτομη Θεολογία, 43.

[13] «καί ἐνεφύσησεν εἰς τό πρόσωπον αὐτοῦ πνοήν ζωῆς, καί ἐγένετο ὁ ἂνθρωπος εἰς ψυχήν ζῶσαν» Gen 2:7.

[14] C. Westermann, Genesis 1-1: A Commentary, trans. John Scullion (Minneapolis, 1984), 147-155.

[15] Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, 147.

[16] St. Theophilus of Antioch, To Autolycus, in Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, 125.

[17] Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, 111.

[18]We are all connected to others because we all share in God’s image.

[19] We need to be in communion with our Creator. See Pentiuc, Jesus the Messiah, 6, 13.

[20] St. Theophilus of Antioch, To Autolycus, in Romanides, The Ancestral Sin, 125

[21] Zimmerli, Ἐπίτομη Θεολογία, 185.

[22] «Ἀδάμ δέ ἒγνω Εὒαν τήν γυναῖκα αὐτοῦ καί συλλαβοῦσα ἒτεκε τόν Κάϊν» Gen 4:1. Biblical texts in English are taken from The Orthodox Study Bible, (St. Athanasius Academy of Orthodox Theology, 2008).

3. The Fall

The story of the fall is clear. Eve was deceived by the serpent[1] and first transgressed God’s commandment by eating the fruit of the forbidden tree.[2] Then she went on and gave to the man who also ate. The punishment is an unavoidable consequence of the act of disobedience. And for woman, it sounds more severe: “I will greatly multiply your pain and your groaning, and in pain you shall bring forth children. Your recourse will be to your husband, and he shall rule over you”.[3]Throughout the primitive history of Genesis, God responds to the rebellion of His creation with a direct judgment and punishment[4]. But God’s justice in the Old Testament is not blind judgment according to a rule that is above those involved. God’s righteousness is divine behavior which is to foster the relationship between Him and His people.[5] Eve took the initiative and, with no hesitation became the leader of a rebellion against God. Thus, a divine prescription was necessary for the healing of an unhealthy situation. “Slavery” came as medicine for an intractable character. Now, contrary to the model of Eve, Christianity offers the model of a “new Eve”, the Theotokos, who offers perfect obedience to God.

Eve’s dialogue with the serpent is “the first theological talk in the narrative.”[6] To Walter Brueggemann’s thought that “the serpent is the first in the Bible to seem knowing and critical about God to practice theology in the place of obedience,”[7] can be added that Eve was the first to practice theology without prayer, which means to talk about God without being in communion with Him. Summarizing the story of the Fall we can say that “in God’s garden, as God wills it, there is mutuality and equity. In God’s garden now, permeated by distrust, there is control and distortion. But the distortion is not for one moment accepted as the will of the Gardener.”[8]

The temptation of Adam & Eve. Pedestal of the statue of Virgin with Child, of Notre-Dame de Paris, CC0

The vast majority of the Fathers in the Orthodox Tradition acknowledge that man and woman were created equal before God and share in His image. A few exceptions arise as a result of differences in understanding of the image of God in humans[9]. Because of the equality of abilities and freedom in the first couple, they both shared the same responsibility for trespassing, according to St. Basil.[10]However for others, Adam’s blame is more serious than Eve’s because she was tempted by a demon while he was enticed by a woman (an equal creature) although he was the one to whom the commandment was given directly by God.[11] After the Fall, the state of the relations between the two humans changed, and woman was punished to be subject to her husband because she had made incorrect use of her freedom and equality. From being a helper to perfection, she became the forerunner in sin.[12]

The distortion in the relationship between the genders occurred immediately after the original sin. Both renounced their responsibility and Adam blamed Eve for his mistake. The “curse” from God upon Eve determined the destiny of the relationship between man and woman throughout human history: “Your recourse will be to your husband, and he shall rule over you.”[13] Indeed, in the Old Testament and the pagan world, the fate of woman was to seek security in man’s love, and his role was to become her master. Even great Greek philosophers placed woman into second place in society, next to slaves.

[1] «καί εἶπεν ὁ ὂφις τῇ γυναικί…» Gen.3:1.

[2]«καί εἶδεν ἡ γυνή, ὃτι καλόν τό ξύλον εἰς βρῶσιν καί ὃτι ἀρεστόν τοῖς ὀφθαλμοῖς ἰδεῖν καί ὡραῖόν ἐστι τοῦ κατανοῆσαι, καί λαβοῦσα ἀπό τοῦ καρποῦ αὐτοῦ ἒφαγε΄καί ἒδωκε καί τῷ ἀνδρί αὐτῆς μετ᾿ αὐτῆς, καί ἒφαγον» Gen.3:6.

[3] «πληθύνων πληθυνῶ τάς λύπας σου καί τόν στεναγμόν σου΄ ἐν λύπαις τέξη τέκνα, καί πρός τόν ἂνδρα σου ἡ ἀποστροφή σου, καί αὐτόςσοῦ κυριεύσει» Gen. 3:16.

[4] Zimmerli, Ἐπίτομη Θεολογία, 222.

[5] Ibid., 181.

[6] W. Brueggemann, Interpretation, a Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching-Genesis,(Atlanta, Georgia, 1982), 47.

[7] Ibid., 48.

[8] Ibid., 51.

[9] According to Theodoretus of Cyrus, the image of God refers to the power of sovereignty (ἀρχικόν) that was not given to the woman. Nevertheless, this task was given to man after the fall. Consequently this characteristic does not refer to the order of creation. See V. Fidas, “Τό Ἀνεπίτρεπτον τῆς Ἱερωσύνης τῶν Γυναικῶν κατά τουςἹερούς Κανόνας” in Οικουμενικόν Πατριαρχείον, Ἡ Θέσις τῆς Γυναικός ἐν τῇ Ὀρθοδόξω Ἐκκλησία καί τά περί Xειροτονίας τῶν Γυναικῶν, Επιμέλεια Αρχ. Γενναδίου Λυμούρη, (Κατερίνη, 1994), 255.

[10] «…Καί ἡ γυνή ἒχει τό κατ’ εἰκόνα Θεοῦ, καί ὁ ἀνήρ. Ὃμοιαι γάρ αἱ φύσεις ἀμφοτέρων ἐπλάσθησαν καί ἲσαι τούτων αἱ πράξεις, ἲσα τά ἒπαθλα, ἲση ἡ τούτων καταδίκη…Ἐπειδή οὖν ὁμότιμον τό κατ’ εἰκόνα εἰλήφασιν, ὁμότιμον ἒχουσι καί τήν ἀρετήν…Ἒχει τοίνυν καί τό θῆλυ, οὐχ ἧττον τοῦ ἂρρενος, καί τό κατ’ εἰκόνα καί τό καθ’ ὁμοίωσιν…» Μ. Βασιλείου, “Περί τῆς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου κατασκευῆς,” Λόγ.Ι, 22-23. PG 30, 33-36.

[11] «ἡ μέν γάρ γυνή, ὑπό δαίμονος καταπαλαισθεῖσα, συγγνωστή ὑπάρχει΄ ὁ δέ Ἀδάμ, ὡς ὑπό γυναικός ἡττηθείς, ἀσύγνωστος ἒσται, ὡς αὐτοπροσώπως τήν ἐντολήν αὐτός ὑπό τοῦ Θεοῦ κομισάμενος» Εἰρηναίου, Fragm. 14, PG 7, 1237.

[12] « (η Ευα) διά τοι τοῦτο γενομένη μέν εὐθέως οὐχ ὑπετάγη…Ἀρχῆς δέ οὐδαμοῦ, οὐδέ ὑποταγῆς ἐμνημόνευσε πρός αὐτήν. Ὃτε δέ κακῶς ἐχρήσατο τῇ ἐξουσία καί ἡ γενομένη βοηθός ἐπίβουλος εὑρέθη καί πάντα ἀπώλεσε, τότε ἀκούει δικαίως λοιπόν΄ ‘πρός τόν ἂνδρα ἡ ἀποστροφή σου’ …» Ἱεροῦ Χρυσοστόμου, “Ὁμ. εἰς Α’ Κορ.” 2. PG 61, 215.

4. Woman in the New Creation. The Early Church

The destiny of humanity changed radically after Christ’s Incarnation, and a living model of human behavior was initiated by the second Adam, the perfect Man, who is Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, Christ’s teaching did not come as a secular revolution. This is what His contemporary Jews did not understand. On the contrary, salvation in Christ came to this world in a silent but powerful way: internally through patience, love, sacrifice, and humility. Although Christ’s teaching introduced a revolutionary model of life where equality, justice, love, and mutual sacrifice are the motives of human behavior, Christ’s Incarnation did not aim for liberation from any social injustice, but liberation from death and corruption. However, people are still dying and this world is more corrupt than ever. The oxymoron can only be understood on a higher level beyond this present world: in God’s Kingdom.

Procession of the Holy Virgins and Martyrs. Mosaic, Ravenna, 7th Century

Jesus’ life and deeds present His sympathy and respect for women and especially for the most neglected women in Judaic society: the adulteress (Jn 8:1-11), the woman that anointed His feet with myrrh (Jn 12:1-8, Mt 26:6-13, Mk 14:3-9), the hemorrhaging woman (Mt 9:20-22, Mk 5:25-34, Lk 8:43-48), and the Canaanite woman whose daughter was demon-possessed (Mt 15:21-28, Mk 7:24-30). Jesus also praises the poor widowed woman and appreciates her gift. He distinguishes Himself from the Judaic tradition according to which women should not have redress to the Law and the Scriptures (Lk 10:38-42). In the above instance, Christ did not indulge in Martha’s criticism of her sister Mary, although Martha was in accordance with the social understanding of a woman’s obligations in the house.

Although Christ honored women, there are no women mentioned among the Twelve, despite the fact that the Gospels often refer to a group of women who follow Christ on His journeys and help him in many practical ways.[1] We should not forget that the myrrh-bearing women demonstrate a dynamic behavior that was not only an indication of their strong faith, but also a sign of their close relationship with Christ. They were the first evangelists, since they were asked by Christ to preach the “good news” to the apostles after His resurrection.[2] These women were considered members of the group of the apostles as stated by Luke (Lk 24:22) and were present at the great events of Christ’s redemptive work: His Crucifixion, Resurrection, Ascension, and Pentecost.

In the Gospels and the book of Acts, we learn that the traditional model of woman accepted by society also prevailed in the life of the first Church. Those who were leaders and took the most responsibilities were men. On the other hand, when women transcended their traditional roles, they were respected by the apostles and the community in general. They were often then given higher positions as co-workers and assistants. Priscilla[3], Lydia[4], and Tabitha[5] were highly appreciated for their work of evangelization and charity. The fact that they were already away from their homes practicing a profession and living far from Jerusalem, a very traditional city, might be parameters to this differentiation of the norm.[6]

St. Paul in his epistles mentions many women as co-workers in his work of evangelization with high esteem among the Christians.[7] He refers to them with special love and respect, and does not make any distinction between them and the men that he also mentions. St. Paul also for the first time refers to a woman deacon[8] and describes the qualifications for this task[9]. In his writings, we also find the information that women were not forbidden to perform work according to the special charisma given them by the Holy Spirit. Thus, there were women prophesying[10] such as the four daughters of the deacon Philip, who are also mentioned as prophets[11] in the book of Acts.

In other instances, St. Paul is very strict with women and adopts the traditional model for women accepted by society. He has been accused of introducing a theology of discrimination against women into the Christian Church. Although he states that “ there is neither male nor female”[12], it is true that in some instances, (especially in 1 Co 11) St. Paul’s language is harsh and gives the impression that he considers women to be in second place to man.

In order to approach this difficult issue and to really understand St. Paul’s theology, one has to consider all the parameters: time, place, and grace. St. Paul’s letters are addressed to specific communities of the faithful, yet they convey the eternal truth of Christ to all generations. The prohibitions for a woman not to pray or prophesize without her head covered[13], nor to speak in the Church[14], and to be subjugated (ὑποτασσόμενη) to her husband[15] (with exception of the sexual relationship between the couple)[16], certainly reflect practices and speculations of the time of the Apostle.

In a similar situation, St. Paul addresses the issue of slaves in the early Church. He does not encourage slaves to rebel against their masters, but on the contrary, he advises them to respect and love their masters “so that the name of God and His doctrine may not be blasphemed.”[17] The fact that in the early Church slaves were respected as equal members of the community and equal citizens of the Kingdom of God does not leave any doubt about the condemnation of slavery as an institution contrary to the Christian ethos. However, the priority for St. Paul is salvation in the given environment so that everyone should be saved[18].

In light of the above interpretation, the prohibitions for women should not be seen as contradicting Christian teaching, but as reflecting the pastoral care of St. Paul to his flock for the salvation of all. He is not inconsistent when on the one hand, he gives advice to the women who prophesize[19] and on the other hand, does not allow women to speak in the Church. The explanation is that in the second case he refers to married women who disrupt the ecclesiastical gathering with immature behavior and have insufficient knowledge on issues of faith[20]. To those women he gives advice to be silent and ask of their husbands at home, as the men have more knowledge of Scripture.

St. Paul also connects the covering of the head with the hair style of women[21] at that time and with the custom common among the Christian communities. The language that sounds harsh to the ears of modern women was the expression of the ethos of that society with one more pastoral parameter. St. Paul was concerned about the influence of pagan religion among Christians. The equality and respect that Christian women enjoyed in the new faith, contrary to the traditional Judaic model, gave such freedom to women that there was a danger of falling into the other extreme, pagan liberality. St. Paul stresses the fact that woman was created by God from the side of Adam, who was created first, as a complete opposite to the notion of idolatrous religion which taught female fertility was the principal creative authority in the world.[22]

The Christian teaching which is the most scandalous to the feminist movement is St. Paul’s call to women to be submissive (ὑποτασσόμεναι) to their husbands. He has been accused of creating a theology of genders that is responsible for woman’s deprivation in the Church. However, to make a fair judgment, it is necessary to examine impartially his overall writings so that the redemptive message of his theology will enlighten and reveal to us the true way of salvation.

[1] Lk 8:1-3.

[2] Lk 24:9-11, Mt 28:9-10, Jn 20:17.

[3] Ac 18:1-3, 18-19, 24-26.

[4] Ac 16:14, 40.

[5] Ac 9:36.

[6] M. Lariou-Drettaki, Η Γυναίκα στην Καινή Διαθήκη, (Αθήνα, 2005), 47.

[7] Rm 16:3-7, 1 Co 1:11, Ph 1: 2, Ph 4:2-3.

[8] Rm 16:1-2.

[9] 1 Tm 3:2-11.

[10] 1 Co 11:5.

[11] Ac 21:8-9.

[12] «οὐκ ἒνι ἂρσεν καί θῆλυ», Gal 3:28.

[13] 1 Co 11: 3.

[14] 1 Co 14: 34, 1 Ti 2:11-12.

[15] Col 3: 18, Eph 5: 22,33, Tts 2:3-5.

[16] 1 Co 7: 1-5.

[17] «ἳνα μή τό ὂνομα τοῦ Θεοῦ καί ἡ διδασκαλία βλασφημῆται», 1Ti 6:1.

[18] «τοῖς πᾶσι γέγονα τά πάντα, ἳνα πάντως τινάς σώσω» 1 Co 9:19-22, «ἀπρόσκοπτοι γίνεσθε καί Ἰουδαίοις καί Ἓλλησι καί τῇ ἐκκλησία τοῦ Θεοῦ, καθώς κἀγώ πάντα πᾶσιν ἀρέσκω, μή ζητῶν τό ἐμαυτοῦ συμφέρον, ἀλλά τό τῶν πολλῶν, ἳνα σωθῶσι» 1 Co 10:23-33.

[19] The prophets in the early Church also had the task of teaching in the ecclesiastical gathering (1 Co 14:1-25).

[20] See more in Lariou-Drettaki, Η Γυναίκα στην Καινή Διαθήκη, 74-76.

[21] 1 Co 11: 13-15.

5. Woman in the New Creation. The “submission”

St. Gregory of Nyssa, in an extensive homily on 1 Co 15:28[1], written to challenge the heresy of Eunomius, explains the various meanings of the word ὑποταγή (submission) in Scripture. He clarifies that the word is used in the case of war to indicate subjugation to the victor, as well as the power of humans over nature and other living creatures. With regard to subjugation, he also mentions slavery where there is unavoidable necessity, and finally, the faithful who submit themselves to God for the purpose of salvation. His point is to differentiate these meanings from that of submission (ὑποταγή) of the Son to the Father. Interestingly enough, in the entire homily St. Gregory does not mention the case of the subjugation of women to men. Possibly he considers the use of the word submission in the case of women, as having the same meaning as the case of the Son’s submission to the Father, something that is also argued by St. John Chrysostom.

Ὑποταγή (submission) of women to men according to St. John Chrysostom[2] is similar to the submission of the Son to the Father and presupposes freedom and ὁμοτιμία (equivalent honor). Chrysostom introduces a revolutionary sociology in the 4th century against the exploitation and degradation of women in the environment of their families. However, with this interpretation he does not attempt to support the destruction of the given order that pertains to the different functions of the persons. He explains this order according to its higher level, which is parallel to the relationship between the persons of the Trinity.

The same commandment to women is also given by St. Peter in his first Epistle[3]. The meaning of the word ὑποταγή is in accordance with that of St. Paul. All Christians are called to respect the given order of society, but in harmony with Christ’s spiritual discipline. This elevates the ethical commandments to a higher level. Women are asked to be submissive to their husbands in order to give them a living example of genuine Christian life, so that those men who are not faithful might be transformed. Men also are called to respect and honor their wives since they are co-heirs (συγκληρονόμοι) of God’s grace and so that the harmonious spiritual life of the two is not disrupted.

In St. Paul’s letter to the Ephesians (5: 22-33) one finds the theological grounds for the essence of marriage, which the Church proclaims in the marital service. The prototype of Christ’s love to His Church is the model that Orthodox theology uses to describe the matrimonial union and the relationship between the spouses. The end of verse 33[4] (nevertheless let each one of you in particular so love his own wife as himself, and let the wife see that she respects her husband)[5] has been misunderstood by women and led to the popular folk custom according to which the bride, at that point of the rite, would step on the foot of the bridegroom as a sign of protest against his power. Contrary to the meaning that society has given to that statement, the pure patristic understanding is expressed by St. John Chrysostom in his tenth homily on Ephesians. He expresses a modern opinion for his age, by saying that fear is appropriate for slaves and sometimes not even for them, but that the woman does not have a true matrimonial bond if she trembles because of her husband.

The epistle reading in the wedding service is Eph. 5: 22-33[6]. This paragraph is preceded by the phrase “submitting to one another in the fear of God”[7] (v. 21). According to the critical editions, this phrase is the beginning of the paragraph v. 22-33, and not the end of the previous one[8]. In this setting, the submission of woman to man is in the spirit of the mutual subjugation that is also asked of all Christians also in other Scriptural references.[9] In 1 Corinthians Paul is repeating the same schema of parallel obedience between man and woman, as between Christ and God the Father.[10]Moreover, according to St. Chrysostom, the image of the man as the head and woman as the body is used to represent the unity of the two in one flesh, not the subordination of the woman.[11]

The interpretation of St. Paul’s writings should not be attempted without consideration of the times and society in and for which it was written. It is true that he balances between the Romeo-Judaic sociological establishment of his time and the new “creation” that Jesus’ Gospel brought to this world. In no case did St. Paul try to contradict this establishment; his vision was to teach his brothers and sisters how to transform their lives through the example of Christ. Thus, he asks women to submit to their husbands as is the social ethos; but more than this he asks men to love their wives with a sacrificial love that is nowhere found in the world, but in Christ. It is a misunderstanding to maintain that the central point of this quote is the submission of women to men, since the message of Ephesians is the mutuality in the relationship between man and woman according to the prototype of the relationship between Christ and His bride, the Church. In this relationship between Christ and the Church one should note that Christ was crucified and died for the Church. The hierarchical placement of man and woman in their marriage has according to St. Paul, this type of theological background. According to the model of Christ and His Church, man is the head of the body of the family as Christ is the head of the body of the Church, the man therefore loves his wife to the point of sacrifice and death for her.

The submission of women to men was established from classic times and was a norm in Judaic culture and its surrounding civilizations. It is obvious in this writing that it does not attempt to call the social order of that time into question, as this is not the message of the “Good News.” The emphasis is that all Christians are asked to put into practice the Christian ethos in order to transform the imperfect reality of this world into the kingdom of God on earth. Admittedly, the main efforts are asked of men, because they are called to go beyond the standards of their time and to respect and honor their wives contrary to the ordinary model of man that was acceptable.

Despite the fact that St. Paul accepts the given social order, that acceptance exists only when the social ethos does not contradict the Christian ethos. Thus, he does not accept the typical model of man who possesses his wife, while he can have extramarital relationships.[12] Origen, who was one of the first interpreters of St. Paul’s letters, considers man and woman as equal with respect to their relationship as a couple.[13] He believes that there is no hierarchy because one belongs to the other, and vice versa. St. John Chrysostom clarifies the apparent contradiction that appears in St. Paul’s letters on the issue of gender in Eph 5:22-33 and 1 Co 7: 1-7. According to him, when St. Paul refers to spiritual topics concerning salvation, virtue, and ethics, there is absolute equality between man and woman. Nevertheless, when St. Paul reflects on social issues, he differentiates the functions and roles, and gives priority to men.[14] The same interpretation is given by Oikoumenios[15], who also believes that in issues of social order and hierarchy man has the priority, but between the couple there is absolute equality.

Theodoretus of Cyrus (5th century) gives a key evaluation on the significance of St. Paul’s writings on the issue of gender. He considers St. Paul as being ahead of his time because he legislates for men contrary to the social establishment and actually supports the equality of man and woman.[16]

Finally, no one can question the equality of men and women on issues of virtue and spirituality, as expressed throughout patristic theology. The Fathers admit that women are athletes of Christ with the same and often greater successes than men.[17]

In the early Christian era, the role and participation of women in the Christian faith is reflected in the writings of contemporary Roman writers. In the second century, the enemy of Christianity, Celsus, calls Christianity “the religion of women”, and Emperor Licinius tries to restrict the new faith by forbidding women from visiting Christian Churches.[18] These testimonies from the non-Christians prove the important place of women in the newly formed Christianity.

[1]Saint Gregory of Nyssa, Η Υποταγή του Υιού στον Πατέρα: Ομιλία Εἰς τό ρητόν «Ὃταν ὑποταγῇ αὐτῷ τά πάντα, τότε καί αὐτός ὁ Υἱός ὑποταγήσεται τῷ ὑποτάξαντι αὐτῷ τά πάντα», (Κατερίνη, 1996).

[2] «Ὣσπερ ὁ ἀνήρ ἂρχει τῆς γυναικός, φησίν, οὓτω καί ὁ Πατήρ τοῦ Χριστοῦ…καί γάρ εἲπερ ἀρχήν ἐζήτει εἰπεῖν καί ὑποταγήν ὁ Παῦλος, ὡς σύ φής, οὐκ ἂν γυναῖκα παρήγαγεν εἰς μέσον, ἀλλά δοῦλον μᾶλλον καί δεσπότην. Εἰ γάρ καί ὑποτέτακται ἡμίν ἡ γυνή, ἀλλ᾿ ὡς γυνή, ἀλλ᾿ ὡς ἐλευθέρα καί ὁμότιμος. Καί ὁ Υἱός δέ, εἰ καί ὑπήκοος γέγονε τῷ Πατρί, ἀλλ᾿ ὡς Υἱός Θεοῦ, ἀλλ᾿ ὡς Θεός. Ὡσπερ γάρ πλείων ἡ πειθώ τῷ Υἱῷ πρός τόν Πατέρα ἢ τοῖς ἀνθρώποις πρός τούς γεγεννηκότας, οὓτω καί ἡ ἐλευθερία μείζων» Χρυσοστόμου, “Εἰς Α΄Κορ.” Ὁμ. ΚΣΤ, 2. PG 51,214-216

[3] «Ὁμοίως αἱ γυναίκες ὑποτασσόμεναι τοῖς ἰδίοις ἀνδράσιν, ἳνα καί εἲ τινες ἀπειθοῦσι τῷ λόγω, διά τῆς τῶν γυναικῶν ἀναστροφῆς ἂνευ λόγου κερδηθήσονται, ἐποπτεύσαντες τήν ἐν φόβω ἁγνήν ἀναστροφήν ὑμῶν…Οἱ ἂνδρες ὁμοίως συνοικοῦντες κατά γνῶσιν, ὡς ἀσθενεστέρω σκεύει τῷ γυναικείω ἀπονέμοντες τιμήν, ὡς καί συγκληρονόμοι χάριτος ζωῆς, εἰς τό μή ἐγκόπτεσθαι τάς προσευχάς ὑμῶν.» 1 Pt 3:1-7.

[4] «πλήν καί ὑμεῖς οἱ καθ΄ἓνα ἓκαστος τήν ἑαυτοῦ γυναῖκα οὓτως ἀγαπάτω ὡς ἑαυτόν, ἡ δέ γυνή ἳνα φοβῆται τόν ἂνδρα»

[5] The translation is not correct because the Greek text refers to “fear” and not to “respect”.

[6]«Αἱ γυναῖκες τοῖς ἰδίοις ἀνδράσιν ὑποτάσσεσθε ὡς τῷ Κυρίω, ὃτι ὁ ἀνήρ ἐστί καφαλή τῆς γυναικός, ὡς καί ὁ Χριστός κεφαλή τῆς ἐκκλησίας…οἱ ἂνδρες ἀγαπᾶτε τάς γυναῖκας ἑαυτῶν, καθώς καί ὁ Χριστός ἠγάπησε τήν ἐκκλησίαν καί ἑαυτόν παρέδωκεν ὑπέρ αὐτῆς. Οὓτως ὀφείλουσιν οἱ ἂνδρες ἀγαπᾶν τάς ἑαυτῶν γυναῖκας ὡς τά ἑαυτῶν σώματα…ἓκαστος τήν ἑαυτοῦ γυναῖκα οὓτως ἀγαπάτω ὡς ἑαυτόν, ἡ δέ γυνή ἳνα φοβῆται τόν ἂνδρα. » Eph 5:20-33.

[7]«ὑποτασσόμενοι ἀλλήλοις ἐν φόβω Χριστοῦ».

[8] See J. Karavidopoulos, “Τά ἁγιογραφικά ἀναγνώσματα τῆς Ἀκολουθίας τοῦ Γάμου: Ἑρμηνευτική προσέγγιση” in the book Ὁ Γάμος στήν Ὀρθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, 140.

[9] «πάντες δέ ἀλλήλοις ὑποτασσόμενοι τήν ταπεινοφροσύνην ἐγκομβώσασθε» 1 Pt 5:5.

[10] «θέλω δέ ὑμάς εἰδέναι ὃτι παντός ἀνδρός ἡ κεφαλή ὁ Χριστός ἐστι, κεφαλή δέ γυναικός ὁ ἀνήρ, κεφαλή δέ Χριστοῦ ὁ Θεός» 1Co 11:3.

[11] «Οὐ γάρ ἐστιν εἷς οὐδέπω, ἀλλ᾿ ἣμισυ τοῦ ἑνός…Γυνή γάρ καί ἀνήρ οὐκ εἰσίν ἂνθρωποι δύο, ἀλλ᾿ ἂνθρωπος εἷς…εἰ ὁ μέν κεφαλή, ἡ δέ σῶμα, πῶς δύο;» “Εἰς Κολασσαεῖς ΙΒ’”, PG 62: 387-388.

[12] «τῇ γυναικί ὁ ἀνήρ τήν ὀφειλομένην εὒνοιαν ἀποδιδότω, ὁμοίως δέ καί ἡ γυνή τῷ ἀνδρί. ἡ γυνή τοῦ ἰδίου σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει, ἀλλ᾿ ὁ ἀνήρ΄ὁμοίως δέ καί ὁ ἀνήρ τοῦ ἰδίου σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει, ἀλλ᾿ ἡ γυνή» 1 Co 7:3-4.

[13] «…μή νομιζέτω ὁ ἀνήρ ἐν τοῖς κατά τόν γάμον πράγμασιν ὑπερέχειν τῆς γυναικός΄ ὁμοιότης ἐστί καί ἰσότης τοῖς γεγαμηκόσι πρός ἀλλήλους» in the article Γεωργίου Πατρώνου, “Γάμος καί Αγαμία κατά τόν Απόστολο Παύλο,” Θεολογία, τόμος NZ, τεύχος 1, 185.

[14] «Ἡ γυνή τοῦ ἰδίου σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει, ἀλλά καί δούλη καί δέσποινά ἐστι τοῦ άνδρός…μηδένα κύριον ὂντα ἑαυτοῦ, ἀλλ᾿ ἀλλήλων δούλους…Εἰ δέ σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει ὁ ἀνήρ ἢ ἡ γυνή, πολλῷ μᾶλλον χρημάτων. Ἀκούσατε ὃσαι ἂνδρας ἒχετε, καί ὃσοι γυναῖκας. Εἰ γάρ σῶμα ἒχειν ἲδιον οὐ χρή, πολλῷ μᾶλλον χρήματα. Ἀλλαχοῦ μέν οὖν πολλήν δίδωσι τῷ ἀνδρί τήν προεδρίαν καί ἐν τῇ Καινῇ καί ἐν τῇ Παλαιᾷ λέγων΄Πρός τόν ἂνδρα σου ἡ ἀποστροφή σου, καί αὐτός σου κυριεύσει΄ὁ δέ Παῦλος διαιρῶν οὓτω καί γράφων΄Οἱ ἂνδρες άγαπᾶτε τάς γυναῖκας, ἡ δέ γυνή ἳνα φοβῆται τόν ἂνδρα΄ἐνταῦθα δέ οὐκέτι τό μεῖζον καί τό ἒλλατον, ἀλλά μία ἡ ἐξουσία. Τί δήποτε; Ἐπειδή περί σωφροσύνης ὁ λόγος ἦν αὐτῷ. Ἐν μέν γάρ τοῖς ἂλλοις πλεονεκτείτω, φησίν, ὁ ἀνήρ΄ἒνθα δέ σωφροσύνης λόγος, οὐκέτι. Ὁ ἀνήρ τοῦ ἰδίου σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει, οὐδέ ἡ γυνή. Πολλή ἡ ἰσοτιμία, καί οὐδεμία πλεονεξία» Ἰωάννου Χρυσοστόμου, “Ὁμιλία ιθ΄,” PG 61, 152.

[15] «Τί δή ποτε δέ ἐν μέν τοῖς ἂλλοις τό πλέον δίδωσι τῷ ἀνδρί ἒνθα περί ὑποταγῆς καί ἐξουσίας ὁ λόγος αὐτῷ, νύν δέ τήν ἰσότητα ἒδωκε; Καί φαμεν, ὃτι ἐκεῖ μέν, περί τοῦ ἀρχικοῦ ὁ λόγος αὐτῷ, νῦν δέ, περί σωφροσύνης, ἐν ᾗ οὐδείς τό πλέον ἢ τό ἒλαττον ἒχειν ὀφείλει» Οἰκουμένιος Τρίκκης, PG 118, 724C.

[16] «”Τῇ γυναικί ὁ ἀνήρ τήν ὀφειλομένην εὒνοιαν ἀποδιδότω, ὁμοίως δέ καί ἡ γυνή τῷ άνδρί”. Περί σωφροσύνης ταῦτα νομοθετεῖ, καί τόν ἂνδρα καί τήν γυναῖκα ἲσως ἓλκειν κελεύων τόν τοῦ γάμου ζυγόν, καί μή ἑτέρωσε βλέπειν καί διαφθείρειν τήν ζεύγλην, ἀλλά τήν προσήκουσαν ἀλλήλοις εὒνοιαν ἀπονέμειν. Τῷ δέ ἀνδρί προτέρω τοῦτο νενομοθέτηκεν, ἐπειδή γυναικός κεφαλή ὁ ἀνήρ. Οἱ μέν γάρ ἀνθρώπινοι νόμοι ταῖς μέν γυναιξί διαγορεύουσι σωφρονεῖν, καί κολάζουσι παραβαινούσας τόν νόμον΄τούς δέ γε ἂνδρας τήν ἲσην σωφροσύνην οὐκ ἀπαιτοῦσιν. Ἂνδρες γάρ ὂντες οἱ τεθεικότες τούς νόμους, τῆς ἰσότητος οὐκ ἐφρόντισαν, ἀλλά σφίσι συγγνώμην ἀπένειμαν. Ὁ δέ γε θεῖος Ἀπόστολος, ὑπό τῆς θείας χάριτος ἐμπνεόμενος, τοῖς ἀνδράσι πρώτοις νομοθετεῖ σωφροσύνην» Θεοδωρήτου Κύρου, “Ἑρμηνεία εἰς τήν Α΄ προς Κορινθίους Ἐπιστολήν” PG 82, 272B-272C.

[17] «Ἀρετῆς δεκτικόν τό θῆλυ, ὁμοτίμως τῷ ἂῤῥενι, παρά τοῦ κτίσαντος γέγονε. Καί τί γάρ ἢ συγγενεῖς διά πάντων τοῖς ἀνδράσιν ἐσμέν; Οὐ γάρ σάρξ μόνον ἐλήφθη πρός γυναικός κατασκευήν, ἀλλά καί “ὀστοῦν ἐκ τῶν ὀστέων”. Ὣστε τό στερρόν καί εὒτονον καί ὑπομονητικόν, ἐξ ἲσου τοῖς ἀνδράσι, καί παρ΄ἡμῶν ὀφείλεται τῷ Δεσπότη» PG 31,241A, ……and «Στρατεύεται καί τό θῆλυ παρά Χριστῷ, τῇ ψυχικῇ ἀνδρεία καταλεγόμενον εἰς τήν στρατείαν καί οὐ διά τήν τοῦ σώματος ἀσθένειαν ἀποδοκιμαζόμενον καί πολλαί γυναῖκες ἠρίστευσαν ἀνδρῶν οὐκ ἒλλατον» PG 31, 624D, ……and «…Ὃμοιαι γάρ αἱ φύσεις ἀμφοτέρων έπλάσθησαν καί ἲσαι τούτων αἱ πράξεις…Μή γάρ προφασιζέσθω τό άσθενέστερον ἡ γυνή· ἐν γάρ τῇ σαρκί τοῦτο· ἡ μέντοι ψυχή ἐπίσης τῇ ἀνδρεία τήν οἰκείαν ἒσχηκε δύναμιν…Ὑπεραίρει γάρ πολύ καί τήν ἀνδρείαν φύσιν ἡ τοῦ θήλεος περί τό ἐνστατικόν τοῦ καλοῦ καί καρτερικόν· καί οὐκ ἂν ποτε ἐξισωθείη ἀνήρ γυναικί ἢ περί τήν τῆς νηστείας καί τήν τῆς ἂλλης ἀρετῆς ἂσκησιν ἢ τό ἐν δάκρυσι δαψιλές ἢ τό ἐν προσευχαῖς φιλόπονον ἢ τό ἐν εὐποιΐαις ἂφθονον…»PG 30,33C-36B.

[18] Barbara Kalogeropoulou-Metalenou, Η γυναίκα στην καθ΄ημάς Ανατολή, (Αθήνα, 1992).

Since physical abuse of women and children was not a rare phenomenon for that era, when St. Basil disqualifies “abuse” as a cause for divorce, he does not refer to women subjected to severe violence. The Church Fathers did not ignore that reality is sometimes hard and far from ideal. The ideal situation is always stressed as the goal for all Christians. However, taking into consideration the real situation, the canons foresee cases in which a marriage is not only destroyed in its essence, but continued cohabitation might be dangerous to one of the spouses’ life. Canon 35 of St. Basil[1] offers the possibility that the woman may leave her husband for a reasonable cause. This canon was combined with two other canons of St. Basil and formed Canon 88 of the sixth Ecumenical Council. St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite, in his commentary on this Canon, accepts the possibility of a woman to leave her husband in case of adultery.[2] Moreover, Justinian’s legislation[3]orders that the woman has the right to divorce her husband in the case where he threatens her life or offends the honor of their marriage by living with another woman, ignoring the warnings of the wife and other people.[4] It is clear in this law, which was also accepted by the Church, that the infidelity of the husband is considered to be a serious reason for divorce only when it is repeated and severe.

Since physical abuse of women and children was not a rare phenomenon for that era, when St. Basil disqualifies “abuse” as a cause for divorce, he does not refer to women subjected to severe violence. The Church Fathers did not ignore that reality is sometimes hard and far from ideal. The ideal situation is always stressed as the goal for all Christians. However, taking into consideration the real situation, the canons foresee cases in which a marriage is not only destroyed in its essence, but continued cohabitation might be dangerous to one of the spouses’ life. Canon 35 of St. Basil[1] offers the possibility that the woman may leave her husband for a reasonable cause. This canon was combined with two other canons of St. Basil and formed Canon 88 of the sixth Ecumenical Council. St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite, in his commentary on this Canon, accepts the possibility of a woman to leave her husband in case of adultery.[2] Moreover, Justinian’s legislation[3]orders that the woman has the right to divorce her husband in the case where he threatens her life or offends the honor of their marriage by living with another woman, ignoring the warnings of the wife and other people.[4] It is clear in this law, which was also accepted by the Church, that the infidelity of the husband is considered to be a serious reason for divorce only when it is repeated and severe.

6. The New Eve

The honor and respect of Christianity to women is demonstrated especially in the person of the Theotokos. She is the human closest to God; after Christ, she is the most beloved and honored person by men and God. She has a great place in worship and is most beloved to the Fathers who wrote extensively about her. St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite affirms that the whole world was created for the person of the Theotokos, and that she was created for Christ. In addition, God would have been pleased by the Theotokos alone, even if the whole of creation had become evil and rebelled against God.[1] The Theotokos is she who: “divinized the human race and brought the earth to the heavens and, on the one hand, made God the son of man and, on the other hand, made people the sons of God as she conceived within herself without seed and ineffably brought forth Him who created all things out of nothing and Him who transforms all things to well being and does not allow them to fall back into nothingness.”[2]

God did not let His beloved creatures feel hopeless after their exile from Paradise. Along with punishment, He offered hope through His promise of the birth of Christ by the Theotokos, by what was said to the serpent[3]:”I shall put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; it will bruise your head and you will strike its heel”[4]. This prophecy is considered the first “good news” to alleviate the pain of exile from Paradise, and expresses the messianic expectation that is fulfilled through the person of the Theotokos.

In Orthodox theology, the typological relation between Christ and Adam is paralleled by that of Eve and the Theotokos. Christ, through His Incarnation, recapitulated all of humanity in its original state as was intended by God’s will from the beginning. He became the New Adam through whom the new generation of humans was born. However, this new creation presupposed the breaking of the shackles of Eve’s disobedience[5] which was brought about through the Theotokos’ obedience (ὑπακοή).[6]

The distinctive role of the person of the Theotokos in God’s plan for the salvation of humanity is the source for the empirical, typological symbolism according to which the liturgical function of women in the plan of divine οἰκονομία is parallel to the work of the Holy Spirit, while the liturgical function of the male is parallel to that of Christ.[7] This does not mean that Orthodox theology tried to ascribe to the Holy Spirit gender characteristics as Russian theological thinking did.[8] On the contrary, the typological relation between the Theotokos and the Holy Spirit is based on the synergy of both in the plan of God’s οἰκονομία.[9] Through the Holy Spirit, the Theotokos became the “temple” of God and type (prototype) of the Church, since the motherhood of the Church and the motherhood of the Theotokos function through the energy of the Holy Spirit.

The Theotokos assists humanity in her Son’s work of salvation. She intercedes for all, because on the Cross He entrusted to her all humankind in the person of his beloved disciple John.[10] She became the spiritual mother of all people as Eve was the physical mother of all humans.[11]

The person of the Theotokos is the most profound example of the recognition of woman’s value in Christian thinking. In his homily on the Nativity, St. Gregory the Theologian affirms that through the birth of Christ from the Theotokos without man’s “help,” Eve pays back her debt to Adam, because Eve was taken from the rib of Adam. From then on, man and woman are equal. However, equality does not mean the lack of distinctive roles and functions of the genders in all aspects of spiritual and social life.

[1] St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite, Συμβουλευτικόν Ἐγχειρίδιον, (Αθήνα, 2001), 314-328.

[2] Γρηγορίου Παλαμᾶ, Ὁμιλία 42, 4, Ἒργα, ΕΠΕ, τομ. 10, σ. 590. «Τό ἀνθρώπινον γένος θεώσασα καί τῆν γῆν οὐρανώσασα, καί υἱόν μέν ἀνθρώπου τόν Θεόν, υἱούς δέ Θεοῦ τούς ἀνθρώπους ποιήσασα, ὡς ἐν ἑαυτῇ συλλαβοῦσα άσπόρως καί Σαρκοφόρον άποῤῥήτως προαγαγοῦσα τόν ἐκ μή ὂντων τά ὂντα παραγαγόντα καί πρός τό εὖ εἶναι μετασκευάζοντα καί πρός τό μή ὂν οὐκ ἐῶντα διαπεσεῖν» (Translated by the author).

[3] See more in Pentiuc, Jesus the Messiah, 34-38.

[4] «καί ἒχθραν θήσω ἀνά μέσον σοῦ καί ἀνά μέσον τῆς γυναικός καί ἀνά μέσον τοῦ σπέρματός σου καί ἀνά μέσον τοῦ σπέρματος αὐτῆς΄ αὐτός σου τηρήσει κεφαλήν, καί σύ τηρήσεις αὐτοῦ πτέρναν» Gen 3:15.

[5] «…Μαρία ἡ παρθένος ὑπήκοος εὑρίσκεται…, ἡ δέ Εὒα ἀπειθής, παρήκουσε γάρ ἒτι παρθένος οὖσα.Ὣσπερ γάρ ἐκείνη, ἂνδρα μέν ἒχουσα τόν Ἀδάμ, παρθένος μέντοι οὖσα…, παρακούσασα, ἑαυτῇ τε καί τῇ πάση ἀνθρωπότητι αἰτία ἐγένετο θανάτου, οὓτω δή καί Μαρία, ἒχουσα τόν προωρισμένον ἂνδρα καί ὃμως παρθένος, ὑπακούσασα, ἑαυτῇ τε καί τῇ πάση ἀνθρωπότητι αἰτία ἐγένετο σωτηρίας» Εἰρηναίου, Κατά αἱρέσεων, ΙΙΙ, 22, 4.

[6] «ὁ τῆς Εὒας τῆς παρακοῆς δεσμός λύσιν ἒλαβε διά τῆς ὑπακοῆς τῆς Μαρίας΄ ὃπερ γάρ ἒδησεν ἡ παρθένος Εὒα διά τῆς ἀπειθείας, τοῦτο ἡ παρθένος Μαρία ἒλυσε διά τῆς πίστεως» Εἰρηναίου, Κατάαἱρέσεων, ΙΙΙ, 22, 4.

[7] See more in V. Fidas, “Τό Ἀνεπίτρεπτον τῆς Ἱερωσύνης τῶν Γυναικῶν κατά τούς Ἱερούς Κανόνας” in the book Ἡ Θέσις τῆς Γυναικός ἐν τῇ Ὀρθοδόξω Ἐκκλησία καί τά περί Χειροτονίας τῶν Γυναικῶν.

[8] Ibid., 268-269.

[9] «Μετά οὖν τήν συγκατάθεσιν τῆς ἁγίας Παρθένου, Πνεῦμα ἃγιον ἐπῆλθεν ἐπ᾿ αὐτήν κατά τόν τοῦ Κυρίου λόγον, ὃν εἶπεν ὁ ἂγγελος, καθαῖρον αὐτήν καί δύναμιν δεκτικήν τῆς τοῦ Λόγου θεότητος παρέχον, ἃμα δέ καί γεννητικήν. Καί τότε ἐπεσκίασεν ἐπ᾿ αὐτήν ἡ τοῦ Θεοῦ τοῦ Ὑψίστου ἐνυπόστατος σοφία καί δύναμις, ὁ Υἱός τοῦ Θεοῦ, ὁ τῷ Πατρί ὁμοούσιος οἱονεί θεῖος σπόρος καί συνέπηξεν ἑαυτῷ ἐκ τῶν ἁγνῶν καί καθαρωτάτων αὐτῆς αἱμάτων σάρκα ἐψυχωμένην ψυχῇ λογικῇ τε καί νοερᾷ, ἀπαρχήν τοῦ ἡμετέρου φυράματος΄ οὐ σπερματικῶς, ἀλλά δημιουργικῶς διά τοῦ ἁγίου Πνεύματος» Ἰωάννου Δαμασκηνοῦ, “Ἒκδοσις ἀκριβής τῆς Ὀρθοδόξου Πίστεως,” 3,2. PG 94, 985.

[10] See more in Jeanlin Francoise, “Ἡ Θέσις τῆς Ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας εἰς τήν Ὀρθόδοξον Ἐκκλησίαν ἐπ᾿ Ἀναφορᾷ πρός τήν Χειροτονίαν τῶν Γυναικῶν” in the book Ἡ Θέσις τῆς Γυναικός ἐν τῇ Ὀρθοδόξω Ἐκκλησία καί τά περί Χειροτονίας τῶν Γυναικῶν.

[11] «Αὓτη ἐστίν ἡ παρά μέν τῇ Εὒα σημαινομένη, δι᾿ αἰνίγματος λαβοῦσα τό καλεῖσθαι μήτηρ ζώντων (Gen 3:20)…Καί κατά μέν τό αἰσθητόν, ἀπ᾿ ἐκείνης τῆς Εὒας πᾶσα τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἡ γέννησις ἐπί γῆς γεγένηται΄ ὧδε δέ ἀληθῶς ἀπό Μαρίας αὓτη ἡ ζωή τῷ κόσμω γεγένηται, ἳνα ζῶντα γεννήση καί γένηται ἡ Μαρία μήτηρ ζώντων. Δι᾿ αἰνίγματος οὖν ἡ Μαρία μήτηρ ζώντων κέκληται» Ἐπιφανίου Κύπρου, “Πανάριον,” PG 42, 728C-732A.

7. The Place of Women in Byzantine Society

Byzantine society was a dynamic union of different cultural elements based on Greek civilization and the Christian faith. Although Christianity was the decisive element in the formation of Byzantium, the practical application of the Christian ethos as a way of life met with the resistance of the old cultural principles that were deeply rooted in the consciousness of the people. Accordingly, the theology of gender as expressed before faced two opposing extremes: the chauvinism of the Roman civilization, which pushed women into the background, on the one hand, and the pagan liberality that was a danger for the social ethos, on the other.

For this society, it is reasonable to say that “the ancient’s interest was order and peace, not blindly equal treatment of man and woman”[1]. The place of woman in the pagan world was reduced to running the household, and bringing up children. Women were always under the rule of their fathers, or their husbands after their marriage.

In Byzantium, girls usually did not attend schools, but from the age of six or seven were taught at home by their parents or tutors. Their education was generally limited to learning to read and write, memorizing the Psalms, and studying the Scriptures. Unmarried young girls spent most of their time in the seclusion of their home, protected from the eyes of foreign men and from threats to their virginity.

Early marriage and procreation were the norm in Byzantium. Marriages were arranged by the parents, for whom the principal considerations were family connections and economic arrangements. Normally, girls accepted the husband selected by their families, although there was occasional resistance, because of the desire of the girl to enter the monastic life or objection to her parent’s choice. Because of women’s inability to choose their husband, the legislators had to deal with a peculiar crime: the abduction of women. Many times the transgression took place with the cooperation of the woman, who in this way imposed her choice on her parents. Yet marriages without parental approval were annulled and became legal only after the parents gave their consent. However, any children born before the marriage was declared valid were considered illegitimate.[2]

The ancient ethos did not allow any margin for sexual relationships before marriage. The civil law ordered the annulment of marriage if the woman was not found virgin by the husband.[3] The rape of a virgin, or even an adulterous affair with one, was punished heavily by civil legislation, but only if the woman was a free citizen. The guilty man faced property penalties, exile, or torture, depending on his social class. The woman was not punished, even if she consented to the act, unless she had been dedicated to the Church or was engaged to another man. The legislator was not interested in the compensation of the woman and did not force the couple to marry, unless both parties and their parents agreed. The fine imposed was only required so as to help the girl marry, although this was almost impossible.[4] On the other hand, the Church’s canons insisted on the marriage of the two individuals since no-one would marry a woman who had lost her virginity; for the same reason, it did not allow the perpetrator to marry another woman.[5] Furthermore, for the woman who consented, the Church canons ordered the same punishment as for the man, which was the penalty exacted for fornication.[6]

In the Roman world women were not equal citizens with men and could not have personal freedom or the right to have a choice. They were under the rule of their father, who was the head of the family. Until the last era of the Roman Empire, women, even after they were married, were under their father’s authority, as fathers even had the right to dissolve their daughter’s marriage.[7] Many women achieved power and status in their middle age after the death of their husband.[8] Widows were no longer viewed as sexual temptresses, and so were treated with respect and trust. Numerous widows achieved financial security by getting total control over their dowries; the most generous Byzantine patronesses were in fact widows who founded churches, monasteries, or commissioned works of art.

Although married women, like their nubile daughters, spent most of their time at home, there were numerous opportunities for them to venture outside. They could go to the public baths or to church for services. They could visit shrines, venerate relics, consult a holy man, or attend religious processions, weddings or funerals. Many women, although excluded for the most part from participation in politics, became passionately involved in the religious controversies of the day, as for example in the iconoclastic controversy.

Even so, respectable women were very careful regarding their public appearances. They avoided the mixed public baths, where many sexual offences were committed, and stayed away from theaters and shows known for their lax morals.[9] A husband even had the right to divorce his wife if she visited those places against his will.[10]

The limited freedom and power of females in the Roman world drove women to become creative in circumventing restrictions, which gave rise to types of crimes. Women resorted, for example, to magic potions and spells to attract the man they wanted, often causing his death. These practices, met with the sharp condemnation of the Canon Law and the sentences for both perpetrators and accomplices were very heavy. St. Basil considers this transgression as premeditated murder, although the man’s death was not intentional.[11]

Women played an indispensable role in the perpetuation of the family line and in the transmission of property from one generation to the next, since the family was the key unit of Byzantine society. This principle determined the way the legislator dealt with transgressions of women. Although Roman law did not consider abortion a crime, since the embryo was considered as part of the woman’s body, it did so in the event the abortion had not been approved by the husband. Abortion, therefore, was not a crime against a life but against the man’s right to have an heir or successor.[12] Thus, civil law gave the husband the right to divorce his wife on account of infertility, something that the Church never accepted.[13] Similarly, adultery was a civil crime because it deprived the husband from having a pure-blooded, rightful descendant. Once again the Church was ahead of its time in condemning the ethos of the society. St. Basil legislated that the same penalty should be issued for abortion as for murder[14], and imposed both to the mother and her accomplices.[15]

Despite the limited freedom of women and the heavy penalties exacted, adultery was not rare in Byzantine society. Nevertheless, it was highly condemned, and in the early centuries of the empire, it was punished with death. Later on, the legislation became more lenient and the penalty was mutilation, cutting off the nose of both guilty parties. The severity of the offence was analogous to the difficulty of the execution of the act. In an environment where women were in seclusion and social life was restricted to the members of the family, extramarital relationships of a woman indicated an immoral character, dangerous for the order of the society. Civil law applied a double standard to adultery: for women, adultery was any extramarital relationship, while men were punished only for engaging in sexual relations with the wife of someone else. A married man’s affair with another woman was called πορνεία (fornication) and was punished only if the woman was unmarried and virtuous. A man could legally engage in physical relations with his own female slaves and concubines, or with prostitutes, but he could not seduce the slave of another man.[16] On the contrary, sexual relationship of a woman, unmarried or not, with her male slaves carried heavy penalties for both parties.[17]

This obvious discrimination of the civil law against women was repeatedly condemned by the Church, but was upheld throughout the length of the Byzantine Empire. Some scholars believe that this attitude had its roots in some metaphysical principles, according to which the person continues living through his descendants, whose genuineness can be affected by infidelity on the part of the woman. Accordingly, female adultery was considered a worse crime than murder because its effects reached into a man’s posthumous posterity[18]. According to Emperor Leo the Wise, this crime affects the life both of the family members and of the offended man’s offspring.[19]

Roman legislation forbade the marriage of a couple that had been condemned for adultery, fearing that such a stipulation might encourage adulterers to murder the woman’s husband, as the last obstacle to enjoying their love.[20] In addition, an adulteress, as a married woman proven guilty by the court, was not allowed to marry anyone else in the future.[21] Because of the peculiar definition of adultery in Roman law, the rule did not apply to guilty men.

Civil law did not allow women to be witnesses in the courts or even admit the adultery for themselves. Only five persons had the right to prosecute the adulteress: the husband, her father, her brother, and two uncles, paternal and maternal.[22] Adultery cases were heard by the civil judicial authorities, while the Church offered a judgment only if the adultery was an impediment to a marriage or the reason for a divorce.[23]

Roman legislation promoted a certain ethical laxity in society by allowing one to have an unlimited number of marriages, contrary to the strong disapproval of the Church. Church canons allow a maximum of three marriages conditioned upon the age of the man: someone with children could not be older than thirty years of age, whereas a childless man could not be older than forty.[24]

Throughout Roman and Byzantine history, the slackening of the social ethos affected the institution of matrimony and gave rise to a high number of cases of what is called “uncontested divorce” (διαζύγιον κατά συναίνεσιν). In a society with loose principles, the spouse had the right to initiate divorce by giving the other spouse a written statement of intent (ἀποστάσιον) in the presence of seven Roman citizens, without any further judicial investigation. This phenomenon is echoed in canonical legislation by the multiple canons that forbid the ordination of men married to these(ἀπολελυμένας) women.[25] The Church through the voice of the Fathers expressed repeatedly her sharp disapproval of this threat to the institution of marriage until the final abandonment of this practice in the tenth century.[26]

[1] P. Mitchell, The Scandal of Gender: Early Christian Teaching on the Man and Woman (Salisbury, MA, 1998), 125.

[2] J. Zhishman, Το Δίκαιον του Γάμου της Ανατολικής Ορθοδόξου Εκκλησίας, trans. Μελετίου Αποστολόπουλου, II (Εν Αθήναις, 1913), 497.

[3]G. Kaouras, Βυζάντιο:Τα Ερωτικά Εγκλήματα και οι Τιμωρίες τους, (Αθήνα, 2003), 77.

[4] Ibid., 73-77.

[5] Canon 67 of the Holy Apostles.

[6]Canon 1 of St. Gregory of Neocaesarea.

[7] Zhishman, Το Δίκαιον του Γάμου, I, 9-11.

[8] A. Talbot, Women and Religious Life in Byzantium, (Burlington, Vermont, 2001).

[9] Kaouras, Βυζάντιο:Τα Ερωτικά Εγκλήματα, 25-48.

[10] Ibid., 47.

[11] Canon 8 of St. Basil.

[12]V. Leontaritou, “Ἐκ γυναικός ἐρρύη τά φαῦλα: Η γυναικεία εγκληματικότητα στο Βυζάντιο” in the book Έγκλημα και Τιμωρία στο Βυζάντιο, Επιμέλια Σπύρος Τρωιάνος, (Αθήνα, 2001), 205-207.

[13] Zhishman, Το Δίκαιον του Γάμου, II, 803.

[14] Canon 2 of St. Basil.

[15] Canon 8 of St. Basil.

[16] S. Troianos, Κεφάλαια Βυζαντινού Ποινικού Δικαίου, (Αθήνα-Κομοτηνή, 1996), 99.

[17] Ibid., 101.

[18]S. Troianos, “Ἡ ἐρωτική ζωή τῶν βυζαντινῶν μέσα ἀπό τό ποινικό τους δίκαιο,” Αρχαιολογία, 10 (1994): 44.

[19] Zhishman, Το Δίκαιον του Γάμου, II, 421.

[20]Ibid., 420.

[21] Ibid., 426.

[22] Ibid., 432-433.

[23] Ibid., 435.

[24] Kaouras, Βυζάντιο:Τα Ερωτικά Εγκλήματα, 153.

[25] Zhishman, Το Δίκαιον του Γάμου, I, 189.

[26] Ibid., 191-201.

8. St. John Chrysostom

Throughout the history of Christianity many voices from the Church rose to protest the established order of society. It is obvious in the patristic writings that the Fathers[1] many times tried to defend the equality of man and woman, demonstrating that discrimination was a problem at all ages. St. Gregory the Theologian, in a revolutionary way, expressed his disapproval to the discriminatory laws against women, saying: “men were the lawmakers, therefore the legislation was against women.”[2]Theodoretus of Cyrus, in the fifth century, stressed the inequality with which the human law treats transgressions of men and women: «for human law compels women to prudent behavior and punishes them when they transgress the law, whereas the same prudence is not required of men, for men were those who set forth the law, but they did not provide for equality».[3]

St. John Chrysostom, an open-minded pastoral teacher, respected women, contrary to contemporary customs, and condemned the sexual misconduct of men that was generally acceptable at the time.[4] Rejecting the beliefs of his society, Chrysostom gave adultery a broader definition, according to the ethos of Christian teachings.[5] As many other Fathers of the Church, he considered any extramarital sexual relationship to be adulterous, whether committed by men or women. He took his definition one step further and condemned even the adulterous intensions and thoughts of men desiring women other than their lawful spouse.[6] Chrysostom encouraged men to disregard the model of man promoted by society, and advised them not to divorce their wives, imperfect as they might be, but to show patience and kindness towards them. Christian men were urged by their pastor to exceed all worldly standards and adopt a new model of life, abandoning the privileges society granted them. These words are striking even in our modern world, where patience is a rare virtue whether it be for men or women. As Chrysostom explained, divorce causes many problems, since a man who divorces his wife will be guilty of adultery if he gets into a relationship with another woman.[7]

Although Christian teaching throughout the Byzantine era and even during the Turkish occupation[8]defended the equality of men and women, Canon Law seems to be inconsistent with this spirit, especially in the canonical work of St. Basil. In our attempt to discern and point out the place of women in the canonical legislation, we have to first acknowledge that Church’s law has a different orientation and principles than civil law. The main difference is that the Church legislates not for the protection of the rights of the people, as is the case with the civil law, but to help the faithful to progress spiritually. Accordingly, while the state emphasized the men’s role in family and society and tried to protect their rights, the Church stressed the role of women as having a greater impact on the spirituality of the family and legislated with this purpose in mind. The same principle applied to the priests, who were expected to have higher moral standards given the great influence they have on the ethos of the Christians in their community, and therefore they were penalized more strictly.

[1]St. Ignatius, St. Athanasius the Great, St. Basil, and others.

[2] «ἂνδρες ἦσαν οἱ νομοθετοῦντες, διά τοῦτο κατά γυναικῶν ἡ νομοθεσία», Λόγος 37,6 PG 36, 289 (translated by the author).

[3] «Οἱ μέν γάρ ἀνθρώπινοι νόμοι ταῖς γυναιξί διαγορεύουσι σωφρονεῖν, καί κολάζουσι παραβαινούσας τόν νόμον΄ τούς δέ γε ἂνδρας τήν ἲσην σωφροσύνην οὐκ ἀπαιτοῦσιν. Ἂνδρες γάρ ὂντες οἱ τεθεικότες τούς νόμους, τῆς ἰσότητος οὐκ ἐφρόντισαν» Θεοδωρήτου Κύρου, “Ἑρμηνεία εἰς τήν Α΄ προς Κορινθίους Ἐπιστολήν,” PG 82, 272B-272C (translated by the author).

[4] «…Ὃταν τοίνυν ἲδης πόρνην δελεάζουσαν, ἐπιβουλεύουσαν, ἐρῶσαν τοῦ σώματος, εἰπέ πρός αὐτήν΄Οὐκ ἒστιν ἐμόν τό σῶμα, τῆς γυναικός ἐστι τῆς ἐμῆς΄οὐ τολμῶ καταχρήσασθαι, οὒτε ἑτέρα τοῦτο ἐνδοῦναι γυναικί. Τοῦτο καί γυνή ποιείτω. Πολλή γάρ ἐνταῦθα ἡ ἰσοτιμία΄καίτοι γε ἐν τοῖς ἂλλοις πολλήν δίδωσιν ὑπεροχήν ὁ Παῦλος», Ἰωάννου Χρυσοστόμου, PG 51, 214.

[5] «Μοιχεία δέ οὐ μόνον τό ἑτέρῳ συνεζευγμένην μοιχᾶσθαι, ἀλλά καί τό δεδεμένον αὐτόν γυναικί», “Α΄ Θεσσαλονικεῖς,” PG 62, 425 and «Πολλοί μοιχείαν νομίζουσι, ὃταν τις μόνον ὓπανδρον φθείρῃ γυναῖκα. Ἐγώ δέ κἂν δημοσίᾳ πόρνῃ, μοιχείαν τό τοιοῦτον εἶναί φημι», “Διά δέ τάς πορνείας…” PG 51, 213.

[6] «Καί ἐκεῖνο μοιχείας ἓτερον εἶδος, τόν γυναῖκα ἒχοντα ἒνδον, πόρναις γυναιξίν ὁμιλεῖν», “Γυνή δέδεται νόμῳ…” PG 51, 222, and «Ῥίζα μοιχείας, ἐπιθυμία ἀκόλαστος. Διό οὐ μοιχείαν κολάζει μόνον, ἀλλά καί ἐπιθυμίαν τήν τῆς μοιχείας μητέρα» “Περί Μετανοίας,” PG 49, 316, and «Ὁ ἐμβλέψας γυναῖκα πρός τό ἐπιθυμῆσαι αὐτῆς, ἢδη ἐμοίχευσεν αὐτήν ἐν τῇ καρδίᾳ αὐτοῦ», “Περί Μετανοίας,” PG 49, 321.

[7] «Κἂν μυρία ἐλαττώματα ἒχη, φέρε γενναίως. Οἶδα ὃσων ἀγαθῶν αἲτιόν ἐστι, τό γυναῖκα πρός ἂνδρα μή διχοστατεῖν. Οἶδα ὃσων κακῶν ἐστιν ὑπόθεσις, ὃταν οὗτοι πρός ἑαυτούς διαστασιάζωσιν. Ἐλαττώματα ἒχει ἡ γυνή; δεήθητι τοῦ Θεοῦ. Ἂν δέ ἀδιόρθωτος μένῃ, σύ τόν μισθόν οὐκ ἀπώλεσας τῆς ὑπομονῆς. Ἐάν δέ ἐκβάλῃς, ἓν πρῶτον ἣμαρτες, τό παραβῆναι τόν νόμον καί μοιχός κρίνεσθαι παρά τῷ Θεῷ», “Περί τοῦ μή ἀπογινώσκειν..” PG 51, 369-370.

9. St. Basil the Great

St. Basil the Great was indeed a great figure in the history of Christianity, a charismatic hierarch with significant contribution in various areas. With concern to our topic, we will examine the pastoral and canonical aspects of his multifarious work. The most important characteristic of his personality is that he had a tremendous education, rare for his time, and was an eloquent speaker. He was a master of oratory and law. His broad education makes his views on issues of law authoritative. Given, however, that St. Basil never wrote in order to satisfy his personal needs[1] or to express abstract theories, but to offer pastoral guidance to his Christian flock and help it progress spiritually, his canons should not be evaluated apart from the rest of his work.

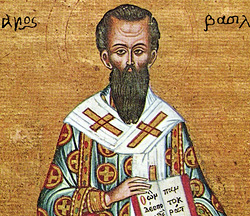

Basil the Great, byzantine Psalter, 11th Century

Throughout his writings it is clear that St. Basil does not support the devaluation of women. He does not exclude women from chanting or from full participation in the liturgical life of the Church[2], and stresses the women’s gift for fasting which he considers to be as natural to them as breathing.[3] He also teaches that obedience to the commandments is an obligation for all Christians.[4] According to St. Basil, the Creator balanced the physical weakness of female nature with the sexual power women have over men.[5] This anthropological observation is the key to understanding St. Basil’s views on issues of ethical misdemeanors of women. Since women have a greater influence on men in physical relationships, they are more accountable for their sexual transgressions. Thus, although St. Basil praises the virtues of women as being the same as those of men, on the issue of sexual transgression he is harsher toward females, possibly because the immorality of women can push men to carnal sin.[6]

On the issue of marriage, St. Basil believes that it is honorable and was given to humans in the act of creation as a way for achieving immortality through their offspring, as well as for companionship and for assisting each other in spiritual growth.[7] Therefore, he condemns any irrational passion that destroys the matrimonial union and is contrary to the purpose of marriage. St. Basil is very negative about divorce[8] and believes that the man who divorces his wife should not be allowed to marry again, just as any woman divorced by her husband should remain single.[9] This ascetic approach to marriage is characteristic of St. Basil’s views on Christian life. His great asceticism permeates all his work, as he tries to inspire Christians to adopt higher standards of life. In view of that, second marriage is seen by St. Basil only as a medication for human weakness, and not as a means for sensual pleasures.[10] Nevertheless, he does not disregard the physical satisfaction of matrimonial life and acknowledges that a good wife is a great blessing for a man.[11] The pastoral care for his flock is obvious in all his writings, including his exegetical work on creation, where he mentions the devastating consequences that a second marriage has on children.[12]

St. Basil’s canonical letters, like all his writings, express his pastoral care, and convey the ethos of asceticism for the spiritual advancement of all Christians. At the same time, however, they are significant legal documents with a lasting influence on the Church throughout her history. These letters became the basis for many canons of the Sixth Ecumenical Council, where St. Basil’s legislation attained canonical authority for the Church.

[1] E. Moutsoulas, “Ο Μέγας Βασίλειος ως Παιδαγωγός”, Μυριόβιβλος,http://www.myriobiblos.gr/texts/greek/moutsoulas_basil.html (accessed February 10, 2010).

[2] P. Christou, Ο Μέγας Βασίλειος-Βίος και Πολιτεία, Συγγράμματα, Θεολογική Σκέψις,(Θεσσαλονίκη, 1978), 82.

[3] «Γυναιξί ὣσπερ τό ἀναπνεῖν, οὓτω καί τό νηστεύειν οἰκεῖον ἐστι καί κατά φύσιν», “Περί νηστείας Β΄,” PG 31, 188B.

[4] «Πάντες ἂνθρωποι ἀπαιτηθησόμεθα τήν πρός τό Εὐαγγέλιον ὑπακοήν, μοναχοί τε καί οἱ ἐν συζυγίαις» PG 31, 628A.

[5] «…διά τῆς μίξεως τό οἰκεῖον μέλος άναλαμβάνειν ταῖς τῆς φύσεως ἀνάγκαις μηχανησάμενος·τοῦτον δέ τόν τρόπον, ἐξ ἑνός δύο, καί ἐκ δύο πάλιν ἓν, τό τε ἂῤῥεν καί τό θῆλυ σαφῶς ἀναδείξας· καί οὐ τήν πρός ἂλληλα συμπλοκήν μόνον, διά τῶν προειρημένων τρόπων, ἡδεῖαν τοῖς σώμασιν αὐτῶν ἐργασάμενος, ἀλλά καί πρός τό ἐκ τῆς συμπλοκῆς ταῖς τοῦ ἒρωτος λαμπάσι διαδουχούμενον γένος, πολύ τό φίλτρον ἐγκατασπείρας…ἡδονῆς ὃλον φάρμακον τῷ ἂῤῥενι τό θῆλυ κατασκευάσας, βιαίοις ὀλκαῖς, καί ἐπί τήν καταβολήν τῆς γονῆς, πρός αὐτό ἂγει τό ἂῤῥεν· οὐχί πρός τό ἂῤῥεν ἂγει τό θῆλυ, ἀλλά τῇ τοῦ θήλεως ἡδονῇ τό ἂῤῥεν πρός αὐτό αἰχμάλωτον ἂγων…Οὓτω τῷ ἀσθενεστέρω ζῲῳ τοῦ Δημιουργοῦ βοηθῆσαι θελήσαντος, ἳνα τῇ ένούσῃ αὐτῷ ἡδονῇ, μαγγανεῦσαι τό ἂῤῥεν, οὐ διά τήν παιδοποιΐαν μόνον, ἀλλά καί δι’ αὐτόν τόν τῆς μίξεως οἶστον, ὑπερμαχοῦν αὐτῷ ἒχῃ τό ἂῤῥεν», “Περί τῆς ἐν παρθενίᾳ ἀληθοῦς ἀφθορίας,” PG 30,676A-C.

[6] «…καί ὣσπερ τά φάρμακα τά διδόμενα πρός ἀναίρεσιν τοῖς ἀνθρώποις, σκοτοῖ τήν σύνεσιν καί ὃλον τόν ἂνθρωπον εἰς ἀναισθησίαν παρασύρει τῇ τοῦ δηλητηρίου ἀποτομία, τῷ αὐτῷ λόγω καί ἡ γυνή διά τοῦ φιλήματος καταβλάπτει τόν λογικόν ἂνθρωπον ἀλόγω ὁρμῇ ὑπαχθέντα…καί…ὣσπερ τι ἂψυχον ὂργανον τῇδε κἀκεῖσε ὃπου βούλεται περιφέρει καί ὣσπερ θάλασσα κυμαίνουσα, ὃλον τό σῶμα ταῖς αὑτῆς ὁρμαῖς παρασύρει. Καί ἒστιν ἰδεῖν…τόν παντοίων ἒμπειρον γραμμάτων ἢ καί τῶν θείων λόγων άναγνώσει ἑαυτόν ἐπιδεδωκότα καί τόν μονήρη βίον πολλάκις ἐπανελόμενον καί Ἐκκλησίας προὒχοντα, ὣσπερ τι ζῷον εὐτελές σχοινίω δεδεμένον, καί ὧδε κἀκεῖ ῥιπιζόμενον…», PG30,817A-C.

[7] «Καί γάρ καί ὁ γάμος αὐτός τοῦ ἀποθνᾐσκειν ἐστίν παραμυθία» PG 32, 1049A, and «…τοῖς δέ ἐξ ἀθανάτων θνητοῖς γενομένοις τήν διαδοχήν τοῦ γένους ἐπισκευάσας, τήν ὡς εἲρηταί που ἀθανασίαν εὑράμενος, καί διά τοῦτο “Αὐξάνεσθε καί πληθύνεσθε” εἰρηκώς…», “Περί τῆς ἐν παρθενίᾳ ἀληθοῦς ἀφθορίας,” PG 30, 780A, and «Τότε γάρ νόμιμος καί κατά τάς θείας Γραφάς συνίσταται γάμος, ὃταν μή πάθος ἡδονῆς προκαταλάβῃ τοῦ νόμου τήν χρείαν, λογισμός δέ τοῦ τε εἰς βοήθειαν ἀναγκαίου καί τῆς τῶν παίδων διαδοχῆς τοῦ γάμου προσθείς τόν σκοπόν, τίμιον ὂντως μνηστεύῃ τόν γάμον», “Περί τῆς ἐν παρθενίᾳ ἀληθοῦς ἀφθορίας,” PG 30, 745C, and «Τί ἐστι τό ἐν Κυρίῳ τόν γάμον συστῆναι;Τό μή προϋποσυρῆναι ὑπό τῶν σαρκός ἡδονῶν πρός τήν μίξιν, ἀλλά κρίσει τοῦ λυσιτελοῦντος πρός τόν βίον, ἑλέσθαι τόν γάμον. Διό καί τό ἀναγκαῖον τοῦ γάμου ὁ Ποιητής έν τῇ φύσει διετάξατο», “Περί τῆς ἐν παρθενίᾳ ἀληθοῦς ἀφθορίας,” PG 30, 748Α.

[8] «…Γυνή συνεκληρώθει σοι κατά τήν κοινωνίαν τοῦ βίου,…ἀναρπασθεῖσα οἲχεται…Μή ἐκπέσης τῶν ὃρων τῆς εὐσεβείας…Εὐγνώμονος οὖν διανοίας οὐκ έπί τῷ χωρισμῷ δυσφόρως ἒχειν, άλλ’ ἐπί τῇ έξ ἀρχῆς συναφεία χάριν τῷ συγκληρώσαντι…» PG 31, 248C-252A.

[9] «Οὐκ ἒξεστι τῷ ἀπολύσαντι τήν ἑαυτοῦ γυναῖκα γαμεῖν ἂλλην, οὒτε τήν ἀπολελυμένην ἀπό ἀνδρός ἑτέρω γαμεῖσθαι», “Ἠθικά,” PG 31,852B.

[10] «Πορνείας παραμυθία ὁ δεύτερος γάμος, οὐχί ἐφόδιον εἰς ἀσέλγειαν», “Ἐπιστ. 160, Διοδώρω,” PG32, 628.

[11] «Γυνή συνεκληρώθη σοι κατά τήν κοινωνίαν τοῦ βίου, πᾶσαν ἡδονήν σοι κατά τόν βίον παρεχομένη, εὐθυμίας δημιουργός, θυμηδιῶν πρόξενος, τά χρηστά συναύξουσα, ἐν ταῖς λύπαις τό πλεῖστον μέρος τῶν ἀνιαρῶν ἀφαιρουμένη», “Εἰς τήν μάρτυρα Ἰουλίτταν,” PG 31,248.

10. St Basil’s contribution to the canonical tradition

In order to evaluate Saint Basil’s contribution to the canonical tradition and spiritual conscience of the Orthodox Church, we have to consider the following presuppositions: First, the canonical writings of Saint Basil are pastoral works that deal primarily with transgressions and aim at restoring the fallen Christian into communion with the body of the Church. The ultimate goal of the legislator is the salvation of the persons committing the transgression and their discipline in such a way as to lead them to repentance while preventing others from entering similar situations. The penances were warning lessons for the whole Christian community and for society in general. The way that we ought to view these rules should be in the spirit of the soteriological work of the Church and not as mere criminal laws.

Second, most of the moral transgressions concerning marriage were also offences in the eyes of civil law, and as such they were treated respectively. The Church distanced herself from the severe regulations of the civil law but in a way that was not contrary to the social ethos, respecting the given cultural establishment. Christianity appeared not as a revolutionary movement that came to overthrow the social order, but as a new way of life with higher moral standards. The respect of Saint Basil for the social establishment is evident in many of his canons, as for example in his eighteenth canon[1] which deals with transgression of a virgin: “it is a great sin for even a slave woman who has given herself up to a clandestine marriage to imbue the house with corruption and roundly insult the owner by her wicked mode of life.”[2]

Finally, the canonical regulations of the Church also served the purpose of preserving the integrity of the Christian communities from the squall of many heresies and deviations from the pure faith. The sixth canon of Saint Basil states: “For this is also advantageous to the Church for safety, and affords heretics no occasion to complain against us on the ground that we are attracting to ourselves on account of our permitting them to sin.” [3]